In June 2018, Mydrim gallery, one of the oldest galleries in Nigeria, organised The Masters Exhibition, a celebration of Nigeria’s art masters who have developed visual arts in Nigeria and made sacrifices for the present generation of artists.

Of the twelve artists exhibited, only one was a woman. Mydrim gallery acknowledged this gender imbalance in its Exhibition Catalogue. According to the invocation for its Exhibition Catalogue, there is a paucity of female Nigerian artists who have risen to the professional master artist threshold. In fact, only one woman has risen past this threshold, Chief Nike Okundaye-Davies, and her works were exhibited, alongside those of the other 11 masters.

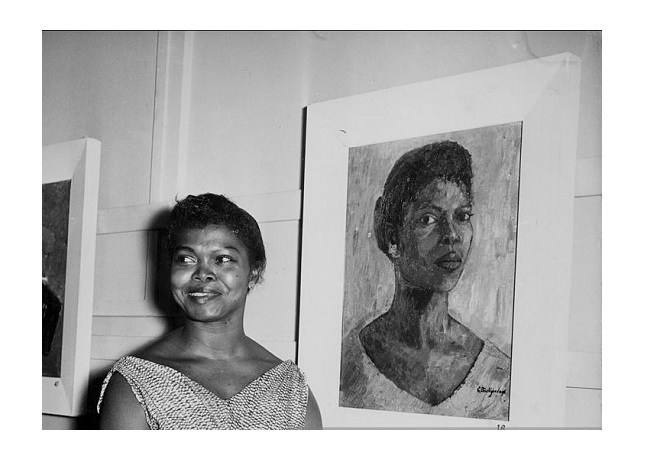

(Credit: pulse.ng)

The Masters exhibition catalogue went on to list the names of three female Nigerian artists, Colette Omogbai, Afi Ekong and Theresa Luck-Akinwale, who almost made the cut, explaining that unfortunately, these women did not have a sustained record of professional practice, or a body of work that could “easily be drawn from for exhibitions of this type”.

Unfortunately, this seems to be the truth. Women artists, where they existed, have mostly dwindled into oblivion. Think of pioneering Nigerian artists. How many can you name? How many of the artists you have named are women? How many of these women’s works are you aware of?

(Credit: postwar.hausderkunst.de)

Let’s take Colette Omogbai- As an undergraduate at the Nigerian College of Arts, Science, and Technology (now Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria), Colette Omogbai organised and carried out her first solo exhibition at the famous Mbari club in Ibadan. After obtaining her Bachelor’s degree in painting in 1965, she moved to Lagos and organised her second exhibition which was heavily vilified by critics and tagged “unfeminine”. Colette responded to her critics in an article titled “Man Loves What Is ‘Sweet’ and Obvious,” which she published in the same year, 1965. However, that was the last recorded exhibition by Colette Omogbai. The only known copy of Colette’s works is Agony, which she created in 1963, before the move to Lagos and the subsequent criticism of her “unfeminine” work.

The absence of materials on the art and life of pioneering Modern Nigerian woman artists such as Clara Etso Ugbodaga-Ngu, Afi Ekong, Colette Omogbai, Theresa Luck-Akinwale and Ladi Kwali has created a gap in our generation‘s understanding of modernist art in Nigeria, and it looks like this void will be repeated for future generations to come.

Don’t agree with me? Do a quick google search for top Nigerian visual artists. How many are female? Going by the results of that google search, if Mydrim Gallery were to organise another Masters Exhibition say, twenty years from now, how many of the exhibited artists would be female?

The disparity between male and female artists in Nigeria is further emphasized by the low participation rates of female artists relative to male artists in organised professional exhibitions, the prevalence of skewed patronage and rewards in favour of male artists, the imbalance in both enrolment of visual art students at various academic levels and graduate turnouts, and the dearth of female artists who’ve achieved the big time, in sales, reputation, academic attention or general acclaim.

(Credit: artstrings.africa)

This disparity is not due to female incapability or lack of artistic feeling. It could perhaps be attributed to the absence of viable professional mentoring among Nigerian female artists. There are not many professional artists capable of, and willing to invest their time in mentoring young female artists.

One artist opines that the gender imbalance in the industry is caused by the harmful biases carried by stakeholders in the industry, which prevents them from supporting female artists and sometimes even leads to the outright exclusion of female artists from some galleries and exhibitions. These biases include the belief that female artists lack staying power, with shaky careers that can easily be destabilized by events like marriage or child bearing, which would result in a change of priorities for these women; or the belief that women artists who seem particularly successful and recognised in the industry actually traded their bodies to secure these opportunities.

Beliefs such as these, serve to alienate women, making it difficult for women to get the sponsorship and support they need to survive and thrive in the close knit industry where gallery representation and exhibition opportunities are gotten via personal networks.

Other reasons suggested for the low success rate of women in the industry include the cultural expectations of women which cause female artists to promote themselves less aggressively, resulting in less representation, less overall exposure less likelihood of entering “the canon” or winning prestigious prizes, and all the other markers that determine art-world success

But what can we do? How do we ensure that female artists are given the same opportunities and encouragement as their male counterparts?

(Credit: Nigeria Magazine)

The first step is to demand for it. On the opening night of MoMa’s exhibition, International Survey of Recent Painting and Sculpture, a show intended to be an up-to-the-minute survey of the most significant contemporary art in the world which included only 14 women among its 169 artists, a group known as WAR (Women Artists in Revolution), a committee of the Art Workers’ Coalition (AWC), picketed the museum, protesting the blatant sexism of the museum and making their demands known. Out of this protest and subsequent revelations of the under-representation of women artists at other museums and galleries, activist artist groups like the Guerrilla Girls were born. These groups helped to draw attention to and engender important conversations about the gender problem in the American art industry, leading to the constant drive for diversity, which has museums deaccessioning art by white male artists in order to make space for female and coloured artists and organising women only exhibitions. We should adapt this model of formation of women focused visual art bodies or groups which would defend the rights of women artists, draw attention to the problems facing women artists and compel museums and galleries to reform their practices. The Female Artists Association of Nigeria (FEEAN) is doing amazing work, but there is room for more organisations. Women need to band together and speak up until their voices are heard and re-echoed across the industry.

Women should be allocated spaces in decision-making positions of organisations like the National Gallery of Arts (NGA), in museum purchases and on selection committees. Putting more women in these spaces would lead to better representation of women artists in exhibitions and higher recognition of women artists. As visual artist, Ayobola Kekere-Ekun put it, the more we get on board, the better positioned we are to have a say in the bus route.

Additionally, women who find themselves in spaces where decisions are being taken, should ensure that they speak up in support of women. Successful women who have fought their way to the upper echelons of the industry should mentor, support and train younger women. They should not be gatekeepers, they should instead hold the door open for the ones coming behind them.

Artists, curators, galleries and other stakeholders in the industry should work to rid themselves of harmful biases and accord young women the same consideration and respect that is given to their male counterparts. The next time you, as a stakeholder in the industry, catch yourself thinking along certain biased lines, stop and deliberately seek to help the object of those thoughts.

There is also a need for existing visual art societies like the Society of Nigerian Artists(SNA) to organize initiatives that support female artists and encourage them to participate fully in their activities. These initiatives could also include conducting research on women unrepresented by galleries and give them the necessary training and promotion needed to find a place. Mentorship arrangements and other initiatives such as regular training and promotion, should be organised and facilitated by these societies in order to help them develop the skills, competence and confidence needed to be at par with their male counterparts. The African Artists Foundation took a step in this direction with the creation of the Female Artists’ Platform which was designed to address the under-representation of women in the Nigerian contemporary art community by encouraging, challenging and developing women interested in visual art, but the last event organised by this platform was in 2016.

(Credit: femaleartistsassociation.com)

Nigerian female artists should learn and practise self-empowerment skills. This involves the development and honing of their artistic skills, their self-awareness and confidence, as well as their self-marketing abilities.

Finally, galleries and museums should implement and sustain various measures to promote gender equality, such as the deliberate accession of art created by and representation of female artists. Of Omenka gallery’s current artist roster, 14% are women- not even close to gender parity, but closer to it than rivals like Thought Pyramid (5%), Hourglass gallery (4%), Alexis galleries (1%) and Mydrim gallery (0%), according to the galleries’ websites.

The world is changing. Women are becoming more competitive and growing in confidence and competence. But in the traditionally discriminatory world of the art industry, women need to work harder and smarter in order to attain professional recognition and overcome decades of marginalization and damage done to the image of the female as an artist. And, in addition to their hard work, we must all go the extra mile to support them and welcome them into these spaces that were previously hostile to women.

1 comment

Good write up. It was due to the in balance in the reports and write ups on female Artists that we started the Female Artists Association of Nigeria. The discrimination is very unfortunate.

Comments are closed.