Growing up in Ipetu Modu, a small town in Osun State, Nigeria, artist Hezekiah Obidare lived surrounded by a cultural richness he once paid no attention to. The town, known for its vast natural deposits of clay, holds a sacred place in Yoruba mythology as the site where Obatala, a messenger from God in charge of creation, moulded not only human heads, but destinies. For most of his life, this story meant little to Hezekiah. Like many young Nigerians caught in the grind of survival, his days were dictated by a routine: wake up early and hustle hard to make ends meet. “I practically lost a sense of self,” he admits. “It was like I had become a machine.”

The question that shook him came unannounced but forcefully: “Who am I?” It was this confrontation with himself that revealed his old way of living and prompted a search for identity that would come to define not only his personhood but his art.

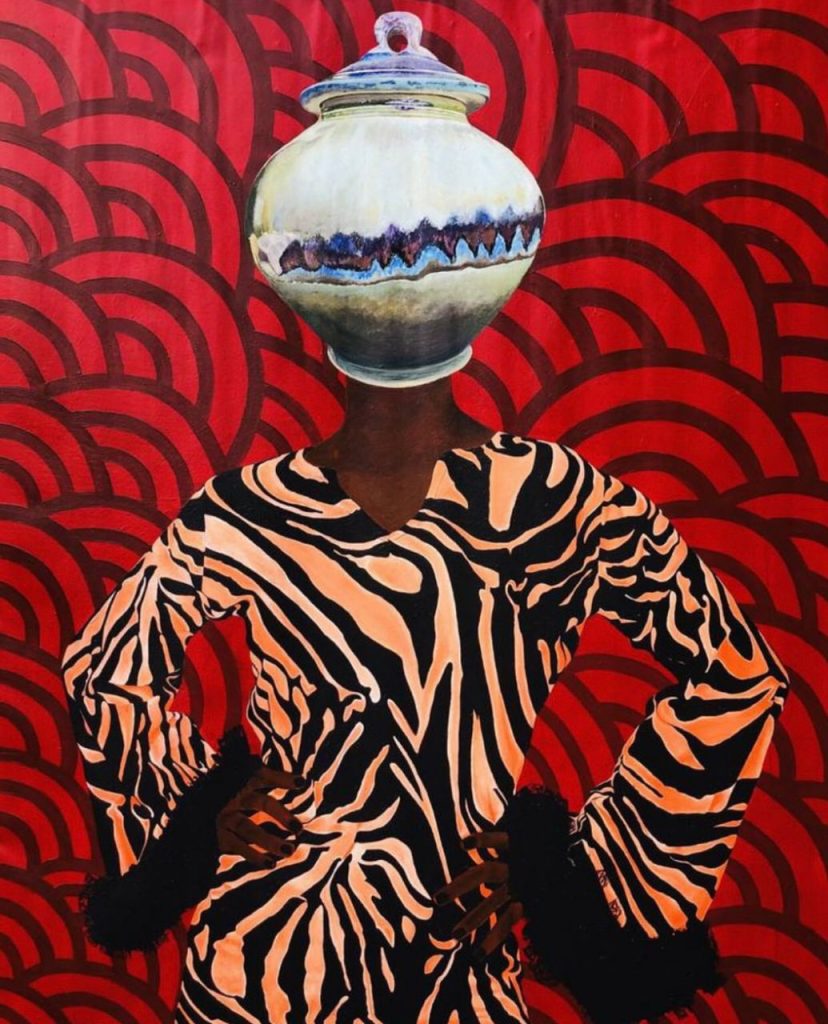

Hezekiah’s practice is rooted in the exploration of identity, both individually and collectively, through the visual symbolism of clay pots placed on the heads of his subjects. In Yoruba cosmology, the head (“ori”) holds profound significance. It is seen as the seat of one’s destiny, a divine compass bestowed at birth. “All we think, all we know, and everything that defines us comes from our heads,” he says. “So, when I put pots on heads, I am not trying to be ornamental; it is symbolic of the identity we carry, of the destinies we were assigned.”

At first glance, the pots may be perceived as curious or surreal. However, for Hezekiah, their meaning is both personal and historical. In the cultural memory of Ipetu Modu and Obatala, clay is more than just a material; it is mythically charged. “So, clay, in that sense, is not just earth; it is the medium of identity. That is powerful.”

But this realisation did not come easily. It took an existential crisis for Hezekiah to pause long enough to look inward. “I had to shut everything down: routine, work, and distractions. I had to focus entirely on finding myself,” he recalls. In practice, this meant abandoning the endless hustle lifestyle he had been living. He returned home to Ipetu Modu, where he immersed himself in the traditions of the town, visiting old pot-making sites, and speaking with lineage keepers of the craft. In retracing the story of Obatala, believed to have trekked miles before settling in Ipetu Modu to mould humans and vessels from its clay, Hezekiah found a mirror for his own journey. By stepping away from survival mode, he reconnected with the roots of creation itself.

The choice came at a cost. As a young Nigerian man, expectations await day in and day out: to provide, to be seen as productive, to keep moving. “Still, I knew that if I didn’t find myself and my identity, then I was just a shadow,” he says. “It was a do-or-die affair.”

That hunger to reconnect with his origins led him into the cultural archives of Yoruba mythology, the symbolic logic of clay, and ultimately the studio. He had always felt drawn to working with clay even before he was aware of its significance. The tangible turning point came when he realized that his hands constantly reached for earth; soil, vessels, pots, as though guided by something larger than himself. Learning that Ipetu Modu’s clay was sacred in Yoruba mythology confirmed this intuition. The story of Obatala molding destinies from that very soil gave him a profound sense of belonging. In that moment, the pull of clay was no longer coincidence but destiny, a spiritual connection between the land and his identity as an artist.

“Looking back, it is like my hands knew something my mind did not yet understand,” he notes. “Now I can explain it, root it in history, and tell a story that inspires others to seek their own truths.”

Today, Hezekiah is best known for his evocative paintings, striking portraits that feature figures bearing earthenware vessels on their heads. These images carry layers of meaning, bridging ancestral myths with contemporary experiences of self-alienation and rediscovery. In Nigeria, where many people are detached from indigenous histories and cultural archives, Hezekiah’s work calls for a return. Not a romantic nostalgia that plays in our memory, but a mindful reconnection. “We live in a country where so many people are just floating,” he says. “We don’t know who we are, or where we come from, and that shows in how we live. When you don’t know yourself, you can’t live intentionally.”

The act of placing a pot on the head becomes, in Hezekiah’s hands, a retrospective act. It forces the viewer to confront questions of meaning, tradition, and self-definition. On the other hand, it invites discomfort. “That is the point,” he says. “I want people to ask, ‘Why is this there?’ And in the process of asking, I want them to start questioning themselves, too. What’s your story? What do you carry on your head?”

Beyond painting, Hezekiah is eager to revisit clay in its rawest form. His plans include sculptural explorations, using clay to tell the same story through an intricate three-dimensional medium. “There is something about the plasticity of clay that excites me,” he says. “It can be soft or hard, fragile or permanent, just like identity. I know I will go back to it fully. It is where the story began, after all.”

For Hezekiah, art is not merely a tool of self-expression; it is a pathway to healing and community-building. He believes that when individuals rediscover themselves, they are better positioned to live with purpose and contribute meaningfully to their society. “We need a community of people who are self-aware, who don’t just move with the tide,” he says. “People who understand their roots, who know why they do what they do.”

His journey as an artist reflects this norm. Trained formally in Fine and Applied Arts, earning both an NCE and a B.A. in the discipline, he has participated in numerous exhibitions in Nigeria and abroad, including shows with Spiralis Gallery in the United States (2023–2024), the Life in My City Art Festival in Enugu, and several editions of the Embassy of Spain’s “Translating Arts into a Common Language,” where he won second prize in 2024. His work has also been featured in group exhibitions in Lagos, Ibadan, and Ondo, as well as online showcases such as Mawuartgallery’s inaugural virtual exhibition. Alongside these, he has attended residencies and workshops, most notably at the Osogbo Artist Village, a historic hub of Yoruba creativity. These experiences have shaped his practice into one that is at once local and global, rooted in myth yet open to contemporary discourse.

His work, then, becomes more than a personal project, it is a call to action. A reminder that finding oneself is not an indulgence but a necessity. That behind every story of identity lost and found lies the possibility of transformation not just for the individual, but for the culture they belong to.