Mark Twain said, “There is no such thing as a new idea. We simply take a lot of old ideas and put them into a sort of mental kaleidoscope.” Every new or original idea is a rearrangement of older ones seen differently. Every art period or movement has been a testament to these words.

Nigerian Modern Art was a period of evolutionary development during colonial and post-colonial times. Artists merged European art techniques with traditional art styles and themes to create a new form of expression that reflected their influences; a merging of the old and new that defined the artists of the period.

One common approach was adapting Western art into local cultural context. This art movement was born in academic institutions, which housed art associations like Mbari Artists and Writers’ Club, Zaria Art Society, and Natural Synthesis Movement.

There are famous adaptations of Western Art by Nigerian creatives. Some of them are The Gods Are Not To Blame by Ola Rótìmí, which was readapted from Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex. Also, there is The Bacchae of Euripides: A Communion Rite written by Wole Soyinka, which was a retelling of The Bacchae by Euripides. The aim of these recreations is to give each creative work a local cultural context, to bring the work closer to its Nigerian audience, and to make it more understandable. One recreation of Western Art that fascinates me is the Stations of the Cross by Bruce Onobrakpeya.

Bruce Onobrakpeya is one of the major figures of Nigerian Modernism. His works often combined indigenous patterns with elements from Western Art. In the 1960s, Father Kevin Carroll, a Catholic priest stationed in Nigeria, commissioned artists to create artworks for the Church. He intended to make biblical stories more understandable through art. One of the works commissioned was the 14-part mural series titled the Stations of the Cross by Bruce Onobrakpeya. The mural was painted at St. Paul’s Catholic Cathedral in Ebute Metta, Lagos. Then, he made linocut prints from the paintings.

The Stations of the Cross is a well-known story in Catholicism. It chronicles the journey and events that led to the crucifixion and death of Jesus Christ. In Catholicism, the stations of the cross were created as a devotion guide for Christians to pray and meditate on Christ’s last days on earth during Lent.

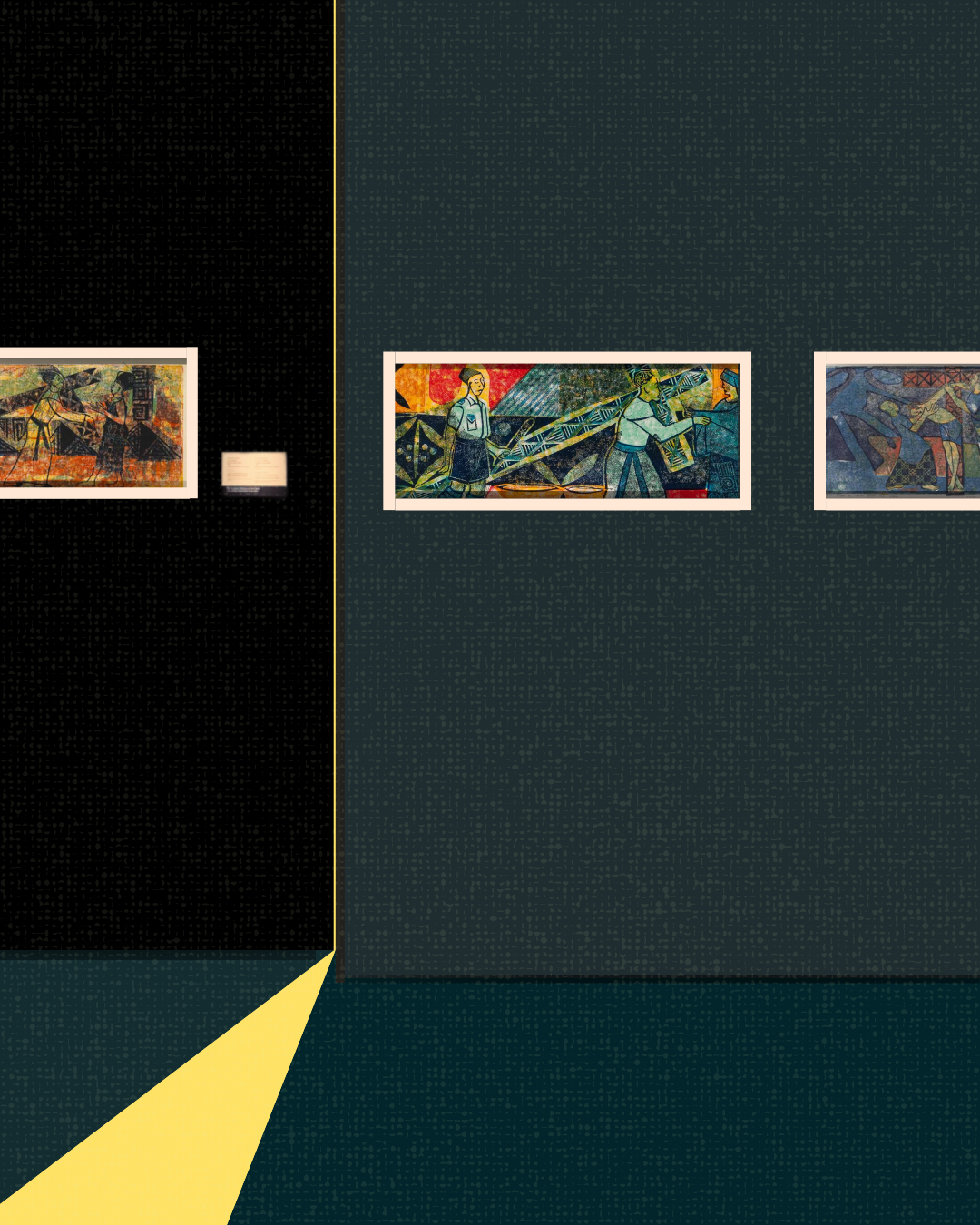

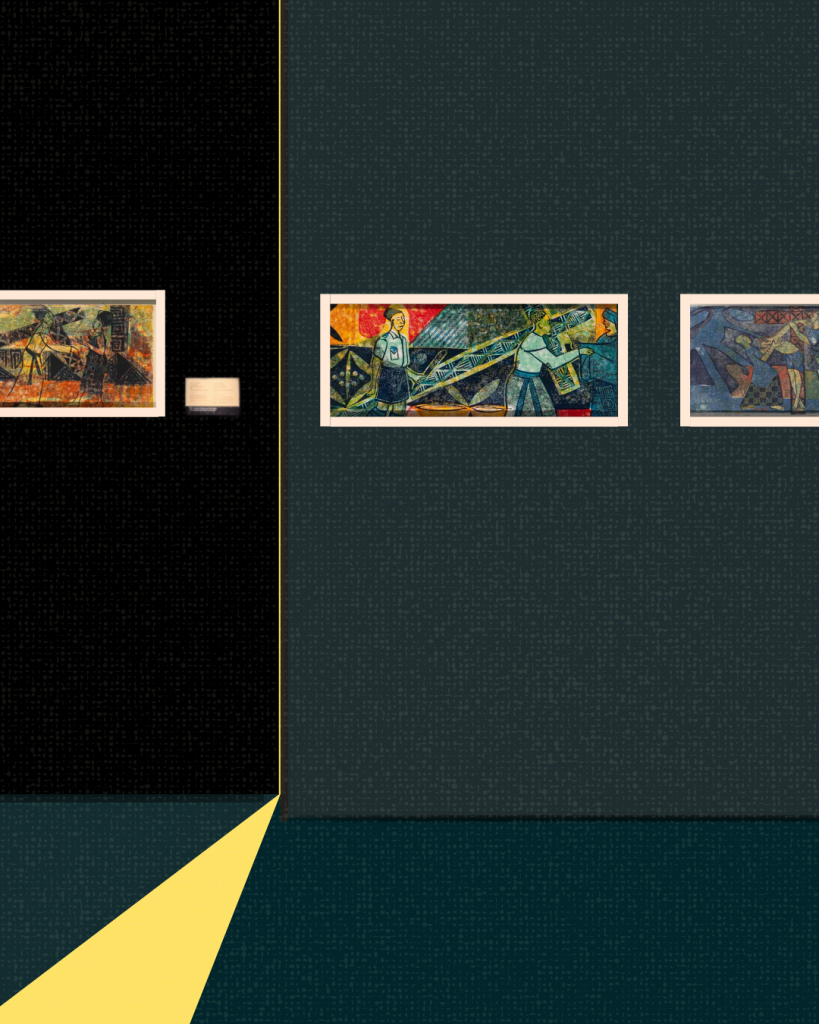

Bruce Onobrakpeya’s creation followed the 14 images rendered in the original Catholic lore. What made his version different was the medium used and his interpretation of the characters in the artworks. Onobrakpeya used linoleum block prints on rice paper with patterns and colours that resembled Adire. Currently, the series is in the collection of the Smithsonian African Art Museum in New Jersey.

The works in this series are characterised by simplistic figures bathed in vivid hues of reds, blues, and yellows. The colours reflect the strong and heightened emotions associated with the events leading up to Christ’s death. The prints illustrated a step-by-step story of Christ’s persecution and burial.

In Onobrakpeya’s work, he reimagined the events and placed the story in a colonial Nigerian context. Jesus and his disciples were Africans garbed in Adire (a fabric made with local dyes in the southwestern part of Nigeria) attire, while the Roman guards were dressed as colonial guards. He did this in a bid to make the story relatable to the Nigerian audience. He brought the story of Jesus Christ’s persecution closer to home. The works explored the themes of colonisation and suffering. Something the Nigerian Christians could relate to, then being under British rule.

The series demonstrates Onobrakpeya’s skill in blending traditional patterns and symbols with the European techniques that were taught to them during formal training. In his interview with Jacoba Urist for the Smithsonian magazine, he said, “I manipulate the characters, the ideas, and the philosophies to bring out the story clearly.”

However, the works didn’t receive the intended reaction. They generated controversy. The members of the Catholic Church in Nigeria criticised the works, saying they misrepresented Jesus Christ. This could mean that Nigerians found it hard to imagine the Saviour to be clothed in the same ordinary attire as them or to even look like them. Perhaps, they preferred to view Jesus’ journey on Earth as an experience distant and different from theirs.

Apart from Onobrakpeya, other Nigerian artists were commissioned to create Fourteen Stations of the Cross for Catholic churches. They’re Lamidi Fakeye and David Dale. Lamidi Fakeye’s version of this work was a series of wood carvings. Like Onobrakpeya, Fakeye was not a Christian. He was a Muslim, yet he received commissions from the Church to carve statues and wooden panels. Another similarity he shared with Onobrakpeya is his interpretation of the work. In his series, the characters had African facial features and wore Yoruba attire (Iro and buba, fila). However, David Dale’s work leaned towards Western art as his resin sculptures lacked African references.

As an artist, Bruce Onobrakpeya explored printmaking techniques and invented new ones. The Stations of the Cross is one of his experimental works, where he combined local motifs and Western elements. Though he was not a Christian, he created numerous Christian artworks through his collaborations with the Catholic Church in the 60s.

Through this series, Bruce Onobrakpeya put his own spin on the classical story of Christ’s persecution and burial. That, I believe, is the goal of a good artistic adaptation: take something old, make it new, and still hold its original essence.